Paris on your plate

By Patricia Unterman

Special to The Examiner

Patricia Wells changed the lives of culinary travelers when she published her groundbreaking "Food Lover's Guide to Paris" in 1984. Finally we had detailed information, in English, that got us to the places that discriminating Parisians (aren't they all?) actually frequented -- not just the bistros and restaurants, but cafés, bakeries, cheese shops, wine bars, tea salons, indoor and outdoor markets. Neighbhorhoods opened up their once-hidden treasures. With Wells' guide in hand, we walked from one arrondissement to the next, eating ourselves silly. As Walter Wells, Pat Wells' teddy bear of a husband and former editor of the International Herald Tribune, said at dim sum lunch the other day, " 'The Food Lover's Guide' was the book that cracked the code."

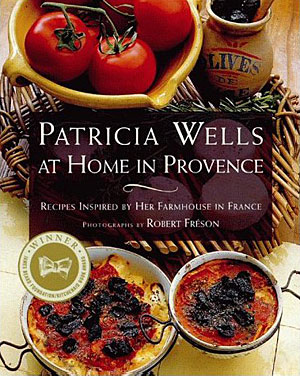

Patricia Wells, her husband, her photographer, Yank Sing owner Henry Chan and I were all eating dumplings as if there were no tomorrow. Maybe Wells was happy to get a reprieve from Parisian cooking, the subject of her latest book, "The Paris Cookbook" (HarperCollins, 2001, $30).

But what I believe is that she's an eater, an enjoyer, someone who gets enormous pleasure from being at the table. Put something well made (as long as it isn't dessert) in front of Wells, whether it be Japanese kaiseki, Shanghai dumplings or choucroute garni, and she digs in appreciatively. There is absolutely no distance between her and her subject. Sound, trustworthy opinion -- based on decades of critical eating and a God-given palate -- is her métier and exactly why you want to buy her books.

If Wells says something is good -- a recipe, a restaurant, a wine, a product -- you can believe her. More than that, she makes you excited about her discoveries. Her descriptions are sensuous yet finely honed. And when Wells writes about Parisian cooking, a subject she knows intimately from having covered it for over two decades, and from turning herself into a skilled home cook herself (she cooked with some of the greats like Joel Robuchon), she takes you way inside the culinary culture. Herein lies the beauty -- and some off the frustration -- of "The Paris Cookbook." Though she successfully adapted recipes from her favorite Parisian restaurant kitchens to the American home kitchen, many of the simplest and most appealing recipes depend on a quality-level of ingredient that is hard to find. (We have beautiful ingredients that cannot be found in Paris, but this cookbook is not about these.)

The meal I cooked from "The Paris Cookbook" could best be described as, well, Parisian. Fat is often celebrated and technique makes the dish. (I think the French stay slim because they eat basically the Atkins diet -- high fat and protein, low carbs -- with lots of red wine to keep the arteries clear.) For an experienced home cook in the Bay Area, the recipes break no new ground, but their French point of view makes them fresh.

I used raw chanterelles that a friend had collected for the green bean, mushroom and hazelnut salad, but I had a hard time finding really fresh hazelnuts. You must use free-range, generously fatted pork loin, not tasteless, unnaturally lean factory-raised pork for Four-Hour Roast Pork. (Next time I'd do the same recipe with a fat-laced piece of pork butt or shoulder for greater moisture.) After the long, slow braise you can eat the meat with a spoon. (It made sublime tacos the next day.)

Alain Passard's Turnip Gratin goes wonderfully with the pork. (But you need two ovens. I tried cooking the gratin long and slow along with the pork, and the turnips never became tender.) As for dessert, wait until our winter Chandler strawberries come in from Santa Maria in February and make the Strawberry-Orange Soup with blood-orange juice. It was a gorgeous and refreshing dish after rich salad, clams (see below), pork and turnips.

Not every recipe translates. For example, you need thick, resonant, tangy French cream, not our monochromatic stuff, to make The Bistrot du DÙme's Clams with Fresh Thyme really fly. This recipe calls for two pounds of rinsed clams in a skillet with 3/4 cup of cream and a teaspoon of fresh thyme leaves. Cover and cook over high heat for 2 or 3 minutes until the clams open. It worked but I didn't think the dish had enough complexity.

It did, however, take on a new demeanor with wine. Though I couldn't get my hands on the "lovely dry Vouvray from the house of Huet" that she drinks with this dish at the Bistro du Du DÙme, I did serve an old Mark West Riesling I happened to have, and the transformation was astounding. The wine completed the dish and the dish expanded the wine, a phenomenon that Walter Wells, a wine appreciator, describes as "2 plus 2 equals 5." If you want to understand all the brouhaha about wine-and-food pairing, follow Wells' recommendations in "The Paris Cookbook." The French invented the alchemy. The right wines really become a key ingredient in French cooking and no one covers this better than Patricia Wells in cookbooks and reviews.

(By the way, The Bistro du Dôme, the source of the clam recipe, is one of my Parisian favorites. I go for aperitif-hour oysters on the half shell at the glassed-in café in front of the mother ship, Le Dôme, on the rue Montparnasse, and then walk across rue Delambre to Le Dôme's affordable and sweet little bistro for grilled sardines and divinely crisp and buttery sole meunière. The fish and shellfish at both places are impeccable, as you can see for yourself at the handsomely tiled fish market that adjoins Le Dôme on the rue Delambre side.)

What excites me about Wells' book is how it evokes place. The recipe/restaurant format presents a way for her to update her brilliant "Food Lover's Guide" without taking on the almost insurmountable task of revisiting and checking all the old places and adding the new. No publisher these days is willing to support an updated guide of this scope, and Wells has had to come up with new ways of packaging the material that she knows best.

"The Paris Cookbook" draws on all her vocations -- as a restaurant critic for the International Herald Tribune, as an ardent food shopper in Paris and Provence where she has a second home, and as recipe writer and cooking teacher. If you never end up cooking from it, you can fruitfully use it as a guide to Wells' current favorite restaurants. Without actually writing about the restaurants you learn a great deal about them from the recipes and the contextual notes. Also laced throughout are tips about Parisian food shops and markets where Wells has found certain ingredients that have inspired recipes. Wells told me that she is working on a Provence cookbook that will be even more like a food-lovers' guide than "The Paris Cookbook."

Even if she is not contemplating a new edition of her "Food Lover's Guide to Paris," she still keeps you abreast of the best on her Web page -- www.PatriciaWells.com -- which apprises fans of her cooking classes in Paris and Provence, reprints restaurant reviews from the Herald Trib, and lists current Wells-approved restaurants in Paris.

What ties together "The Paris Cookbook" and every other piece of Wells' output is her eye for authenticity. She doesn't care for the trendy, international-style restaurants that have sprung up in Paris during the past decade. She supports the local, the small, the artistic. Whether we get information through cookbook, guide, Web page or newspaper column, it really doesn't matter. What we want to know are Patricia Wells' opinions and inside tips about the food and wine of France, however she lets us in on them.

RECIPES

Gallopin's Green Bean, Mushroom and Hazelnut Salad

(Le Salade de Haricots Verts, Champignons et Noisettes de Gallopin, from Gallopin)

2 servings as a main course; 4 servings as a first course

I last sampled this classic bistro salad at the colorful Gallopin, just across the street from the Paris bourse, or stock market. This is the sort of dish that depends upon freshness and care all around. It's hearty enough to serve as an entire luncheon meal, or as a first course as part of a major bistro feast.

4 tablespoons fine sea salt

8 ounces green beans, rinsed and trimmed at both ends

8 ounces fresh mushrooms, wiped clean, stems removed, thinly sliced

1 small shallot, peeled and finely minced

About 3 tablespoons minced fresh chives

3 tablespoons freshly toasted hazelnuts, coarsely chopped (see Note)

Hazelnut Vinaigrette

1 tablespoon best-quality sherry wine vinegar (or best-quality red wine vinegar)

Fine sea salt to taste

3 to 4 tablespoons best-quality hazelnut oil (or extra-virgin olive oil)

Equipment:

A large pasta pot fitted with a colander

1. Prepare a large bowl of ice water.

2. Fill a large pasta pot, fitted with a colander, with 3 quarts water and bring to a boil over high heat. Add the 4 tablespoons salt and the beans, and cook until crisp-tender, about 5 minutes. (The cooking time will vary according to the size and tenderness of the beans.) Immediately remove the colander from the water, allow the water to drain from the beans, and plunge the colander into the ice water so the beans cool down as quickly as possible. As soon as the beans are cool (no more than 1 to 2 minutes, or they will become soggy and begin to lose flavor), drain them and wrap them in a thick towel to dry. (The beans can be cooked up to 4 hours in advance. Keep them wrapped in the towel, refrigerated if desired.)

3. In a large bowl, combine the green beans, mushrooms, shallot, chives and toasted hazelnuts. Set aside.

4. Prepare the vinaigrette: In a small bowl, combine the vinegar and sea salt. Whisk to blend. Add the oil, whisking to blend. Taste for seasoning.

5. At serving time, pour the vinaigrette over the salad. Toss gently to blend, and serve.

Note: Toasting nuts imparts a deep, rich flavor: Preheat the oven to 350 degrees F. Spread the nuts on a baking sheet, and toast in the oven until fragrant and evenly browned, about 10 minutes.

Alain Passard's Turnip Gratin

(Gratin de Navets Alain Passard, from ArpËge)

4 to 6 servings

Each Saturday morning in Le Figaro, chef Alain Passard offers an incredible assortment of recipe ideas revolving around a particular ingredient. One day in February the subject was Cantal, the rich golden cheese of the Aubergne mountains. He suggested this preparation, which I promptly followed. This vegetable gratin is delicious on its own with a tossed green salad, or as a vegetable accompaniment to a roast chicken, roast pork or veal.

1 1/2 pounds round spring turnips, peeled and cut into thin rounds

Sea salt

Freshly ground black pepper

4 ounces cow's-milk cheese, such as Cantal or Cheddar, coarsely grated

1 1/2 cups whole milk

1/2 teaspoon fresh thyme leaves

Equipment:

A 2-quart gratin dish

1. Preheat the oven to 400 degrees F.

2. Butter a 2-quart gratin dish, and in it layer half the turnips. Season well with sea salt and black pepper, and then layer half the cheese. Season that layer. Repeat with the remaining turnips and the remaining cheese, seasoning well after each layer. Add milk just to cover. Sprinkle with the thyme and more sea salt and pepper. Place the dish in the center of the oven and bake until the turnips are soft and have absorbed most of the milk, 1 to 1 1/4 hours. Serve immediately.

FrÈdÈric Anton's Four-Hour Roast Pork

(Le Roti de Porc de Quatre Heures de Frederic Anton, from Le Pre Catelan)

8 to 10 servings

Over the past several years, braised meats have become increasingly popular among Parisian chefs: Rare lamb, rosy pork, duck with a touch of pink all have their place, but the homey, wholesome flavors of meat and poultry cooked until meltingly tender and falling off the bone are once again in vogue. Here FrÈdÈric Anton, chef at the romantic restaurant PrÈ Catalan in the Bois de Boulogne, offers universally appealing roasted pork loin, flavored simply with thyme. This is delicious accompanied by sautÈed mushrooms or a potato gratin.

One 4-pound pork loin roast, bone in (do not trim off fat)

Sea salt to taste

Freshly ground white pepper to taste

2 teaspoons fresh or dried thyme leaves

4 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

3 tablespoons unsalted butter

2 carrots, peeled and finely chopped

2 onions, peeled and finely chopped

6 plump, fresh cloves garlic, peeled and minced

2 ribs celery, finely chopped

2 cups homemade chicken stock

2 large bunches of fresh thyme sprigs

Equipment:

A large heavy casserole with a lid, or Dutch oven

1. Preheat the oven to 275 degrees F.

2. Season the pork all over with sea salt, white pepper and the 2 teaspoons thyme. In a large heavy-duty casserole that will hold lthe pork snugly, heat the oil over moderate heat until hot but not smoking. Add the pork and sear well on all sides, about 10 minutes total. Transfer the pork to a platter and discard the fat in the casserole. Wipe the casserole clean with paper towels. Return the pork to the casserole, bone side down. Set it aside.

3. In a large, heavy skillet, combine the butter, carrots, onions, garlic, celery and sea salt to taste. Sweat -- cook, covered, over low heat without coloring -- until the vegetables are soft and cooked through, about 10 minutes. Spoon the vegetables around and on top of the pork. Add the chicken stock to the casserole. Add the bunches of thyme, and cover.

4. Place the casserole in the center of the oven and braise, basting every 30 minutes, for about 4 hours, or until the pork is just about falling off the bone. Remove the casserole from the oven. Carefully transfer the meat to a carving board and season it generously with sea salt and white pepper. Cover loosely with foil and set aside to rest for about 15 minutes.

5. While the pork is resting, strain the cooking juices through a fine-mesh sieve into a gravy boat, pouring off the fat that rises to the top. Discard the vegetables and herbs.

6. The pork will be very soft and falling off the bone, so you may not actually be able to slice it. Rather, use a fork and spoon to tear the meat into serving pieces, and place them on warmed dinner plates or a warmed platter. Spoon the juices over the meat, and serve. Transfet any remaining juices to a gravy boat and pass at the table.

Strawberry-Orange Soup With Candied Lemon Zest

(Soupe de Fraises à l'Orange au Zeste de Citron Confit)

6 servings

All it takes is an intelligent combination of fresh ingredients to create a dish with a sophisticated and pleasing dimension: The sweet, fruity flavor of strawberries reaches another realm, enlivened by a touch of vinegar, sweetened with the intensity of freshly squeezed orange juice, and brought to a crescendo topped with a touch of zesty, candied lemon peel. There are just a few days in March when blood oranges are still in the market and the first strawberries of the season make their debut: That's when this dessert is at its peak. The rest of the year, make this dish with the best juice oranges you can find.

1 pound fresh strawberries, rinsed, stemmed and quartered lengthwise (or into sixths if very large)

1 tablespoon best-quality red wine vinegar, sherry vinegar or balsamic vinegar

4 tablespoons sugar

The Candied Lemon Zest

Zest of 1 scrubbed lemon, cut into fine slivers

1/4 cup sugar

1 1/4 cups freshly squeezed blood orange juice (about 5 oranges) or juice of top-quality juice oranges

1. In a large bowl, combine the strawberries, vinegar and sugar. Stir gently. Cover securely with plastic wrap and refrigerate for 1 hour.

2. Meanwhile, prepare the cnadied lemon zest: Place the zest in a medium-size saucepan, add 1 cup cold water, and bring to a rolling boil over high heat. Remove from the heat and drain the zest in a small fine-mesh sieve. Rinse with cold water, and drain.

3. In a small saucepan, combine the blanched lemon zest, the sugar and 1/4 cup water. Stir to dissolve the sugar. Bring to a simmer over very low heat and cook until the zest is transparent and just a thin veil of syrup remains, 8 to 10 minutes. Remove from the heat and let the zest cool in the liquid.

4. At serving time, add the orange jiuce to the strawberry mixture. Mix gently. Pour the strawberry soup into shallow individual bowls or flat-bottomed champagne glasses, known as coupes. Garnish with the candied lemon zest, and serve.